When I started recording stories that my grand father used to tell me about his career as a make up artist in the Hindi film industry from 1941 to roughly 1995 little did I realize that the process would be so enriching. It was enriching not only because it added to my understanding of film history but also because it made me question my methodology to research. I would very often lose my patience with my grand father because he was someone I could lose my patience with: unlike a formal subject- researcher relationship. At the outset of the research project he had made it clear to me that he had to be the “hero” of the story and that I should not portray him as an also ran.

So I started with my protagonist, his stories and an old dictaphone. Given papa ajoba’s background in theatre, he would start acting, enunciating when I turned on the recording device. Many a times I would ask him to retell stories and he would repeat them verbatim, as if they were rehearsed. The facts he did not want to me to record at all, were the scandalous affairs that that various actors had. The gossip was kept out of his stories for as long as the dictaphone was on. Once I put it off, stories of how a glamorous actress’ husband came looking for her in the make up room because he suspected her of having an affair with a superstar of the time or how one day, a senior star after drinking too much ended breaking the bones of two brothers on the same night, came to the fore. I think papajoba was very conscious of the fact he must tell these stories “properly”.

I was able to take him to meet two of his favorite stars, Sadhana and Shammi Kapoor. The reason I wanted to meet these two was that I was interested in seeing the power dynamics between a ‘make up artist' and the ‘star’. With Sadhana, the camaraderie was obvious; in fact papaajoba hardly let her speak. He continued to tell his stories, many of which I had heard over the last several months. I was irritated at first but slowly through the course of the interview realised what he said to me at the beginning of this project, “I don’t want to be an also ran,” I realized that maybe for the first time he is centre of attention in front of her. This project is about him, she had to merely add to the stories not be the focus. It’s also the first time she realized that he knows a lot more technically and his memory is far better than hers, he is 85 and she is about 69. With Shammi Kapoor, the exchange was warm but he was clearly the ‘star’ and gave us just 30 minutes of his time and no more. He spoke to the point, offered us tea and packed us off after reciting a poem about himself written by Kamlesh Pandey, admittedly all very dramatic.

The other interesting thing I noted was that my grand father not only added ji before every actresses name but for all the men he added sahib so he called Shammi Kapoor, Shammi sahib, S. Mukherjee (the producer at Filmistan) Mukherjee sahib, the villain Pran was also called Pran sahib and on so on. The other technicians who were older than him or his seniors he referred to as dada for e.g. Mr.Paranjpye, the make up artist who papaajoba began his career with was called Paranjpye dada or the make up artist at Prithviraj Kapoor’s theatre, was also referred to as More dada. Mr.Jagtap the sound recordist at Filmistan again was called Jagtap dada. I think this differentiation was to do with class and stature and not so much just age or seniority. All the people he called sahib were clearly from a higher social strata and were actors, directors, producers. The term dada was more a term of endearment to someone he respected or was senior but either was a technician or from the same socio-economic background as my grand father. For e.g.Dhumaal the comedian who worked as a part of my great grand father’s theatre company was called Dhumaal dada. Of course with younger stars like Dharmendra, Sanjeev Kumar, Rajesh Khanna, papa ajoba referred to them by their first names. This is my observation, that while he was at Filmistan this was some sort of an unwritten norm but after the studios started to close down and technicians became freelancers they didn’t have a strict protocol to follow.

I have no doubt in my mind that the process of recording the stories was extremely worthwhile and as it often happens with stories: we started getting an audience. And it would happen that my friends would drop by to listen to his narrative while I was recording. And sometimes they would continue sitting with papa ajoba long after I had finished my work and the stories would continue into the night. There was one on Rajesh Khanna’s chamchas, which my friends recall with pleasure and papa ajoba narrated it sparing almost no expletives in the Hindi language. The point is that this project was not researched in the conventional manner: in fact the idea of just listening to the story is what drove it.

There are varied methodologies that can be used and I have always found the more unconventional ones exciting. For example, I started my career as a production assistant with an upcoming filmmaker. In the initial months of my job I was sent to find C-grade film producers in the underbelly of Bombay. Not armed with much except the excitement of a rookie, I scavenged the streets of Oshiwara in Andheri where young ‘wannabe’ starlets frequented one-room-kitchen offices of production houses: that was my field for research and the books I was told to refer to were film trade magazines like Super Cinema, Box Office and of course Complete Cinema. This was in essence my first tryst with film research or serious research of any kind. Before this, the research I had done was for college projects, mostly from the library or the internet and a few interviews with ‘subjects’ for a student documentary.

I am indebted to my first boss for putting me through the grind of looking for material in the dark and sometimes dangerous world of the Hindi C-grade film industry. I could not have asked for a more challenging subject or a research methodology so different, where I almost always, had to take up pseudonyms while conducting interviews and more often than not lied about my motive. Those were days when ‘taking your subject into confidence’ meant nothing and a little cheating went a long way in unearthing the truth, well almost. Little did I realise at the time that this was my first brush with recording film history or my active engagement as a researcher of that part of the film industry that often gets overlooked for a more mainstream history.

It was this interest in recording a second rung film history that made me record my grand father’s stories. But I was concerned throughout the recording process of my relationship to my subject. At a level it was even worrying: was I doing what most documentary filmmakers do, point their cameras at the subjects and ‘frame’ them and pretend to tell their story? This was one crucial reason why I did not want to video record him but used a dictaphone instead. The idea of ‘framing’ my grand father was an uncomfortable thought. But the question that kept troubling me was: can one be a detached, unobtrusive recorder? In my case I was not detached but in fact passionately attached to my “subject”. I was terribly intrusive, always telling my subject to speak loudly, or speak in Hindi rather than Marathi and sometimes even forced him to recognise people in photographs that he could not. This was a conscious process (the bickering, the cajoling), the attempt at creating the ‘real’ relationship between me and my grand father, in this case also a researcher and her subject.

I also realised that because of the fellowship, I had given time to just listen to what an 85 year old man from the film industry had to say. I wish I had given that much time to my paternal grand father who worked for the railways during the British rule, who knows what insights one might have gained. Or better still what if I had chatted longer with both my grand mothers about feminism in their times or simply recorded their stories. It is these stories that start the construction of tradition. The idea that I have a tradition of theatre and cinema in my family shapes who I am today. But tradition is loaded word, even dangerous perhaps: who decides what turns into a tradition and what does not.

This is perhaps the reason tradition has to be re-looked at ever so often. It also needs frequent questioning in order to make place for newer narratives, lesser heard voices. I hope with my grand father’s story one has perhaps been able to add another voice from the periphery of the Bombay film industry. But this voice is not adequate in discovering a newer cinema history or even challenging the traditional film history but it is an attempt. This project is a start for me as researcher to probe further, look deeper for unexcavated stories from the past.

Finally this project has been a process of discovery of family ties, long lost homes and of course of forgotten people and their lives.

Tuesday, September 8, 2009

Monday, June 8, 2009

Happy Birthday to you Papa Ajoba

Today papaajoba turns 88: a colourful life of films, joy and struggle. Here's wishing him a great birthday with a song from a film he was the make up man on for his favorite actress Sadhana.

Happy Birthday to you.

Happy Birthday to you.

Monday, February 2, 2009

Debashree's Interview with papa ajoba

Ever since I moved to Bangalore I have not been able to do anymore work with my grand father for this blog. But once in awhile somebody sees this blog or meets me somewhere and wants to meet papaajoba and sometimes like Debashree Mukherjee they want to meet him for their own research.

When Debashree asked me if she could interview my grant father I was more than happy, my only condition was that she should share her interaction, learnings,insights on this blog. She agreed and below is the transcript of her interview with papaajoba.

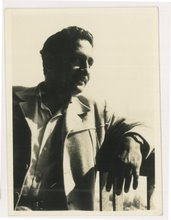

P.S. This is papa ajoba's latest photograph taken by Debashree.

*********************************************

Excerpts From An Interview with Ram Tipnis, 18th August, 2008, at his Bandra residence

This interview was conducted as part of my M.Phil research on the Hindustani film industry in Bombay during the 1930s and 40s. One of my areas of focus is a cluster of film studios of the time, particularly Filmistan. A friend suggested that I take a look at Anuja’s blog and I’m still thanking her for that piece of timely advice! Filmistan studio was founded in 1943-44 by a breakaway group from the famous Bombay Talkies Ltd.; a move spearheaded by Sashadhar Mukherjee and Rai Bahadur Chunilal. This interview tries to understand certain material practices and individuals associated with Filmistan in the 1940s.

Mr. Tipnis’ story is significant not just as an account of an earlier time, but also because it is an unlikely voice. While there is a paucity of published research on the early years of the talkies in Bombay, the little that exists has had to depend on official studio sources or interviews with star actors and directors. It is rare to find the voice of a make-up artiste in a context wherein even cinematographers and editors do not receive any journalistic or scholarly attention.

The interview was conducted in a mix of Hindi and English, and I have used my discretion to translate Mr. Tipnis’ words. A lot of the material in this interview might overlap with material already on the blog. But then, memories often have a cyclical, repetitive nature. These notes are part of my ongoing research and are presented here verbatim. I am grateful to Anuja Ghosalkar, and her mother, Nayana Ghosalkar, for facilitating this conversation. And of course, much gratitude to Mr. Tipnis, for sharing his memories with such felicity.

DM: When and how did you join Filmistan?

RT: Filmistan started in 1942-43. At the time I was working as a make-up artiste at Shantaram’s Rajkamal Studio. I had some minor misunderstanding with V. Shantaram one day and tempers flared. He shouted at me and I, being young and hot-headed, just quit. I don’t know if it was bad luck or good, but that’s what motivated my move to Filmistan. I knew a character actor of the time, Nana Palsikar, who had done work with Bombay Talkies and knew the Filmistan gang. He wrote me two recommendation letters - one to be given to Rai Bahadur Chunilal, the Managing Director of Filmistan Ltd., and the second to be given to Mr. Sashadhar Mukherjee, the Controller of Productions. I went to Filmistan the very next day, armed with my letters. Both the men met me and asked me some questions. Then they called their own make-up artiste, Mr. Jadhav. Rai Bahadur asked him: “Do you know this young man?” And Jadhav replied, “Yes.” Jadhav was an old and experienced make-up artiste who had worked for Marathi theatre as well. He knew my father, a stage actor, and was familiar with my work.

And so, in 1945, at the age of 25, I officially joined the Filmistan team. S. Mukherjee told me that they had started work on a film titled Shikari and they needed special Chinese make-up for one of the characters. He suggested that I take on the make-up work for the film, supervised by Mr. Jadhav. The actor playing the role was Samson, who generally played the villain in most films. I did a trial for the Chinese look on him and we went to Rai Bahadur and S. Mukherjee. They loved it. Rai Bahadur said, “Arrey! He is Chinese!” So I was now officially on board and doing my own film.

…

Shikari was directed by Savak Vacha, the sound recordist at Filmistan. He belonged to the Sashadhar Mukjerjee group and had come with him from Bombay Talkies…

DM: What was it that went wrong at Bombay Talkies?

RT: See, after Himansu Rai passed away, the studio was managed by Devika Rani. Amiya Chakravarty was her preferred director, and maybe Sashadhar Mukherjee felt sidelined. I don’t know exactly, but there was some misunderstanding. So Sashadhar Mukherjee, Ashok Kumar, Rai Bahadur Chunilal, Dattaram Pai, Gyan Mukerjee and Savak Vacha left Bombay Talkies and started their own Filmistan Studio. S. Mukherjee started his career at Bombay Talkies as a sound recordist and then learnt the ropes of filmmaking. He was very good at his work. Rai Bahadur Chunilal was a great man. I can vouch for the fact that if he had lived for another 10 years, the film industry would have been transformed. His son, by the way, was Madan Mohan.

DM: Do you remember any of the Filmistan writers? There used to be this writer called Manto…

RT: Yes. I remember him, but never had much contact with him. He was from the Writing Department so I would just see him around. Sometimes he would come on the sets during a shoot. You might know that he also acted in a Filmistan film, Eight Days…

DM: As an Air Force Officer?

RT: As a pagal! He was a good man. Every artiste has his ideas. He soon left for Pakistan…

DM: Were Rajkamal and Filmistan very different in terms of work atmosphere?

RT: Rajkamal Studio was like a Junior College for artistes. I was doing independent pictures at that time, when Rajkamal started. The man who did their make-up was my guru and he suggested that I join them. I was earning Rs. 150 outside but accepted the Rajkamal job for Rs.75 – because Rajkamal was a school, Shantaram was an artist. There was discipline, but another kind of discipline. Like don’t go there, don’t do that. But it was a school. We learnt how to create make-up material at Rajkamal. Now we know the procedure.

Filmistan was like a higher college, Senior College, very different but very fine. Rai Bahadur would come every day at quarter to two, without fail. Never a minute’s delay. That used to be lunch time so he would eat a bit and then take his rounds of the studio at 2pm. That was a time of the day when no one would be outside. Even the artistes would be in their rooms. One day he happened to be on a round as I was getting out of the toilet. He looked at me and kept walking. After some minutes his office boy came and called me saying Sir wants to see you. I wondered what was going on but hurried to his office. Rai Bahadur said that he was disappointed in me. “You are a Senior Officer of this company, the Head of a department, how can you be so careless?” I was completely taken aback. Then he told me that he had noticed that my trousers were still unbuttoned when I got out of the toilet! Such a small thing, but its these details that make an impression. That was their kind of discipline.

I remember another incident. In those days, Max Factor, the US make-up company, was the only established brand making professional products. So we all used to buy our basic materials from them. I used to personally go to their office at Gateway of India to pick up stuff. Rai Bahadur again summoned me one day and said that as an Officer of the company I should not travel by second-class on the local train. It is a question of the company’s reputation. So he got me a First-class pass.

Again, another time, an assistant of mine applied for a salary increment. Rai Bahadur called me and asked me if I agreed to it. See, at Filmistan, the Head of a department was the ultimate authority. He was entitled to take all decisions regarding his team and his requirements. So I said yes, the boy had not received an increment last year either and deserved one. Rai Bahadur then asked me how much the boy was getting at the moment. I told him, Rs. 50. Immediately he issued an order to the Accounts office to increase the salary to Rs.100. So that’s how they worked. There was a good atmosphere and good relations between the bosses and us.

At Filmistan we often used to play cricket, all of us. There was a big ground behind the studio. They were proper matches, being announced the day before. One day, Kishore Sahu was shooting for the picture Sindoor. He was a bald man and in those days we did not have very fine wigs. So I used to apply hair on his head. That day there was a cricket match scheduled for 11 and Sahu’s shoot was at 2pm. I reached the studio as usual at 8am and soon met Sahu. He asked me if I was playing in the match that day. I told him how can I when he has a shoot. He said, “Do one thing, do my make-up now and then go play your match!” It was perfect. Later I met S. Mukherjee on the pitch and he asked, “Kyon? Aaj shoot nahi hai kya?” I told him I had already finished for the day and they were all amazed. Because that hair job is intricate work. Anyway, the point is that everyone was very friendly and we were equals. On the set you have to be alert. When it is time for duty, you give it your best. But off-duty, no one will question you.

DM: Did you have any fixed timings for work at Filmistan?

RT: I used to reach the studio at 8am every morning. The artistes would come by 8.30-9am and the shoot would start by 10am. If there was no shoot on any morning, we would sit, chat, play cards or make material. And there was no compulsion to stay in the studio if we had no work. We just had to inform someone that we were done with our work and would leave. There was no system of freelance at the time. Even an actor like Dilip Kumar was paid a monthly salary like us. The 15th of every month was payday and Dilip Kumar would have to stand in the line just like the rest of us! I used to get paid Rs.500 per month and my assistants would get Rs. 200 and Rs. 100 respectively.

DM: Was the studio shooting more than one film at a time?

RT: Initially, for the first 4-5 films, Filmistan would shoot one film after the other was finished. Then we started double pictures with films like Shehnai (?)

DM: Did you also have female assistants on your make-up team?

RT: No no. The females were in the Hair Dressing department. That was a separate job. In fact Bombay Talkies and Filmistan started the trend of having a separate Hair Department. Before that the actresses would get their maids to do their hair or everyone would just do their own hair, you know Indian style.

DM: Wasn’t there a separate Costume Designer in those days?

RT: See nowadays people go about calling themselves “Costume Designer” but they just pick clothes without even reading the script! Earlier they would do a meeting with the Director, the Art Director and the Tailor Master and they would decide what costumes to give the main actors. I will show you 3 photographs of 3 actresses from today’s movies and you tell me what is different about each. They all have the same make-up, same hair, same clothes! In my time, Meena Kumari was Meena Kumari and Sadhana was Sadhana.

DM: Do you remember women being hired in any other department?

RT: Only as actresses or in the Hair department. Nowhere else. Even in the Costume department we had men, tailor masters. Sometimes if they needed help they might call the Hair assistant, but no, there were no other women employed in the studio. See, I have traveled all over the world and there are ladies in other countries who do make-up, who write and even do camera. But not in India. Now they are trying, as make-up artistes. Initially our union opposed this. Why you know? Because they are not used to the odd hours.. we are prepared to work not just 4-5 hours but even 12 hours if required. New people come in and have different ideas. Also, in our Indian culture, it was not accepted for a woman to come in so much contact with men.

DM: At the time you joined the film industry, was there a very negative view taken of the cinema world, as a disreputable place?

RT: No, no. I started my career in Pune and there was a very good atmosphere in the Marathi industry. In Bombay it was there. There were stories of film people drinking, smoking. And also earlier the ladies who joined films were not from good backgrounds. Durgabai Khote, Shobhana Samarth, Nalini Jaywant, they started a new trend. They were well-educated girls.

DM: How did you prepare for a film?

RT: Once the script was ready and the actors were finalized, I would be briefed by the director about the story and each character. I would then discuss my ideas for each character. Mostly these discussions would be with S. Mukherjee or directors like Gyan Mukherjee, Nandlal Jaswantlal, Santoshi etc.

DM: As far as scripts were concerned, were directors working with complete scripts before shooting started or would scenes continue to be written while production was on?

RT: S. Mukherjee always worked with a complete screenplay, with dialogue. There would be routine discussions on set, but everything was planned as far as possible.

DM: Because the ‘bound script’ as a concept has only recently come back into practice in Bombay.. For the longest time it was routine practice to present actors with new scenes on set.

RT: Haan, we used to call it ‘daily rationing’!

DM: Himansu Rai had a clear policy about hiring graduates, educated youngsters. Did this ethos get carried over into Filmistan as well?

RT: Himansu Rai was a very educated man from a high family. He got the best trained technicians, foreign technicians for his studio. In Filmistan there weren’t any special requirements as such. If you suit the character, you will be hired. (vague)

DM: This was a time of great political turmoil and communal tension. Independence and Partition were looming. Did this atmosphere affect life at the studios?

RT: At the time, 42-45, I was at Rajkamal. There was nothing of the sort.

DM: Manto writes about Filmistan being threatened with arson, around 46-47, because of the large numbers of Muslims who were employed…

RT: No no no. There was nothing like that. Dekho, film industry ek aisi industry hai jahaan na koi Hindu na Muslim. Sab artistes aur workers hain.

DM: Was there any anxiety about the Partition in terms of talented people leaving for Pakistan? Of technicians, artistes etc. leaving the Bombay film industry?

RT: Not that I remember. In fact, so many people from the Lahore film industry came to Bombay. Also, many people who left, came back after some time.

DM: How much did Hollywood influence work at the studios? Did you pick up techniques and trends from those movies or from American magazines?

RT: We used to watch the films that came and try to understand, study anything new or innovative. But that was our only source, the films. For example, there was a film with this man [Fred Astaire in Royal Wedding, 1951] who is dancing in a room and during the sequence he starts dancing on the walls and ceiling! Our sound recordist said he would figure it out. He made a model of a room, with pulleys and things, so that the character would be standing or dancing in one place but the whole background will be moving! It created the same effect but it was never picturised.

DM: What about Hollywood magazines? Didn’t people read technical magazines for information?

RT: They were simply not available. Maybe some people could pick them up on their travels..

DM: Which were the main halls in the 1940s for English film releases?

RT: Metro, Regal, Empire..

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)