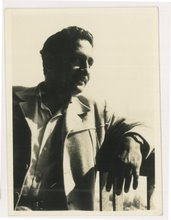

When I started recording stories that my grand father used to tell me about his career as a make up artist in the Hindi film industry from 1941 to roughly 1995 little did I realize that the process would be so enriching. It was enriching not only because it added to my understanding of film history but also because it made me question my methodology to research. I would very often lose my patience with my grand father because he was someone I could lose my patience with: unlike a formal subject- researcher relationship. At the outset of the research project he had made it clear to me that he had to be the “hero” of the story and that I should not portray him as an also ran.

So I started with my protagonist, his stories and an old dictaphone. Given papa ajoba’s background in theatre, he would start acting, enunciating when I turned on the recording device. Many a times I would ask him to retell stories and he would repeat them verbatim, as if they were rehearsed. The facts he did not want to me to record at all, were the scandalous affairs that that various actors had. The gossip was kept out of his stories for as long as the dictaphone was on. Once I put it off, stories of how a glamorous actress’ husband came looking for her in the make up room because he suspected her of having an affair with a superstar of the time or how one day, a senior star after drinking too much ended breaking the bones of two brothers on the same night, came to the fore. I think papajoba was very conscious of the fact he must tell these stories “properly”.

I was able to take him to meet two of his favorite stars, Sadhana and Shammi Kapoor. The reason I wanted to meet these two was that I was interested in seeing the power dynamics between a ‘make up artist' and the ‘star’. With Sadhana, the camaraderie was obvious; in fact papaajoba hardly let her speak. He continued to tell his stories, many of which I had heard over the last several months. I was irritated at first but slowly through the course of the interview realised what he said to me at the beginning of this project, “I don’t want to be an also ran,” I realized that maybe for the first time he is centre of attention in front of her. This project is about him, she had to merely add to the stories not be the focus. It’s also the first time she realized that he knows a lot more technically and his memory is far better than hers, he is 85 and she is about 69. With Shammi Kapoor, the exchange was warm but he was clearly the ‘star’ and gave us just 30 minutes of his time and no more. He spoke to the point, offered us tea and packed us off after reciting a poem about himself written by Kamlesh Pandey, admittedly all very dramatic.

The other interesting thing I noted was that my grand father not only added ji before every actresses name but for all the men he added sahib so he called Shammi Kapoor, Shammi sahib, S. Mukherjee (the producer at Filmistan) Mukherjee sahib, the villain Pran was also called Pran sahib and on so on. The other technicians who were older than him or his seniors he referred to as dada for e.g. Mr.Paranjpye, the make up artist who papaajoba began his career with was called Paranjpye dada or the make up artist at Prithviraj Kapoor’s theatre, was also referred to as More dada. Mr.Jagtap the sound recordist at Filmistan again was called Jagtap dada. I think this differentiation was to do with class and stature and not so much just age or seniority. All the people he called sahib were clearly from a higher social strata and were actors, directors, producers. The term dada was more a term of endearment to someone he respected or was senior but either was a technician or from the same socio-economic background as my grand father. For e.g.Dhumaal the comedian who worked as a part of my great grand father’s theatre company was called Dhumaal dada. Of course with younger stars like Dharmendra, Sanjeev Kumar, Rajesh Khanna, papa ajoba referred to them by their first names. This is my observation, that while he was at Filmistan this was some sort of an unwritten norm but after the studios started to close down and technicians became freelancers they didn’t have a strict protocol to follow.

I have no doubt in my mind that the process of recording the stories was extremely worthwhile and as it often happens with stories: we started getting an audience. And it would happen that my friends would drop by to listen to his narrative while I was recording. And sometimes they would continue sitting with papa ajoba long after I had finished my work and the stories would continue into the night. There was one on Rajesh Khanna’s chamchas, which my friends recall with pleasure and papa ajoba narrated it sparing almost no expletives in the Hindi language. The point is that this project was not researched in the conventional manner: in fact the idea of just listening to the story is what drove it.

There are varied methodologies that can be used and I have always found the more unconventional ones exciting. For example, I started my career as a production assistant with an upcoming filmmaker. In the initial months of my job I was sent to find C-grade film producers in the underbelly of Bombay. Not armed with much except the excitement of a rookie, I scavenged the streets of Oshiwara in Andheri where young ‘wannabe’ starlets frequented one-room-kitchen offices of production houses: that was my field for research and the books I was told to refer to were film trade magazines like Super Cinema, Box Office and of course Complete Cinema. This was in essence my first tryst with film research or serious research of any kind. Before this, the research I had done was for college projects, mostly from the library or the internet and a few interviews with ‘subjects’ for a student documentary.

I am indebted to my first boss for putting me through the grind of looking for material in the dark and sometimes dangerous world of the Hindi C-grade film industry. I could not have asked for a more challenging subject or a research methodology so different, where I almost always, had to take up pseudonyms while conducting interviews and more often than not lied about my motive. Those were days when ‘taking your subject into confidence’ meant nothing and a little cheating went a long way in unearthing the truth, well almost. Little did I realise at the time that this was my first brush with recording film history or my active engagement as a researcher of that part of the film industry that often gets overlooked for a more mainstream history.

It was this interest in recording a second rung film history that made me record my grand father’s stories. But I was concerned throughout the recording process of my relationship to my subject. At a level it was even worrying: was I doing what most documentary filmmakers do, point their cameras at the subjects and ‘frame’ them and pretend to tell their story? This was one crucial reason why I did not want to video record him but used a dictaphone instead. The idea of ‘framing’ my grand father was an uncomfortable thought. But the question that kept troubling me was: can one be a detached, unobtrusive recorder? In my case I was not detached but in fact passionately attached to my “subject”. I was terribly intrusive, always telling my subject to speak loudly, or speak in Hindi rather than Marathi and sometimes even forced him to recognise people in photographs that he could not. This was a conscious process (the bickering, the cajoling), the attempt at creating the ‘real’ relationship between me and my grand father, in this case also a researcher and her subject.

I also realised that because of the fellowship, I had given time to just listen to what an 85 year old man from the film industry had to say. I wish I had given that much time to my paternal grand father who worked for the railways during the British rule, who knows what insights one might have gained. Or better still what if I had chatted longer with both my grand mothers about feminism in their times or simply recorded their stories. It is these stories that start the construction of tradition. The idea that I have a tradition of theatre and cinema in my family shapes who I am today. But tradition is loaded word, even dangerous perhaps: who decides what turns into a tradition and what does not.

This is perhaps the reason tradition has to be re-looked at ever so often. It also needs frequent questioning in order to make place for newer narratives, lesser heard voices. I hope with my grand father’s story one has perhaps been able to add another voice from the periphery of the Bombay film industry. But this voice is not adequate in discovering a newer cinema history or even challenging the traditional film history but it is an attempt. This project is a start for me as researcher to probe further, look deeper for unexcavated stories from the past.

Finally this project has been a process of discovery of family ties, long lost homes and of course of forgotten people and their lives.

Tuesday, September 8, 2009

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)